Since its founding as the Cumberland Valley Normal School in 1871, Shippensburg University always has had an integrated student population.

Segregation of blacks and whites in Shippensburg’s public school system, though, did not end until the Great Depression.

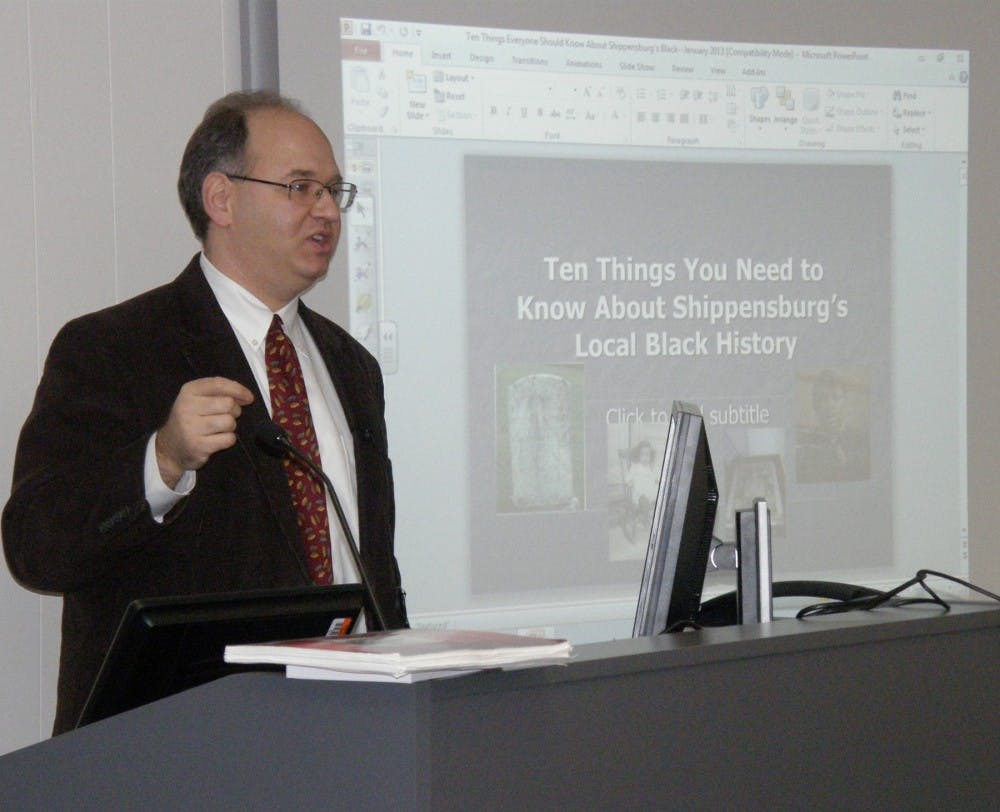

Steven Burg, chairperson of SU’s history department, shared that and other facts about local black history during a Feb. 20 talk at Ezra Lehman Memorial Library.

More than 75 students, faculty and local residents attended Burg’s presentation, held as part of the university’s recognition of Black History Month.

While SU never was segregated, “there were periods in its early history when no African-American students were visible in photos from the time. But they were not barred from attending,” Burg said.

There were some rules regarding their attendance, however, such as being required to live off campus.

“They lived in boarding houses in town, as did some white students,” Burg said.

Shippensburg was settled in 1730, making it the oldest town in the Cumberland Valley. Evidence of a number of blacks in the area — in the form of more complete tax rolls, on which local residents listed servants and slaves as part of the property they owned — began appearing consistently in the 1760s.

In 1780, Burg said, there were 15 slaveholders and 47 slaves living in Shippensburg. That was the year Pennsylvania abolished slavery — the first state to do so.

“Abolition was popular in Eastern Pennsylvania, but not in this part of the state,” Burg said.

Despite that, slaveholders in the eastern section of the state did not always free their slaves.

“There were people in Philadelphia who sold their slaves to people in Central Pennsylvania. At one time, Cumberland County had the largest number of slaves in Pennsylvania,” Burg said.

Signs of the earliest black community in Shippensburg still exist near campus, according to Burg.

The Locust Grove Cemetery on North Queen Street was established as a burial spot for slaves, and then became a free black cemetery.

There are 26 black veterans of the Union army during the Civil War, eight of whom were born in Shippensburg and are buried in Locust Grove.

A historical marker at the front of the cemetery property denotes the first site of the African Methodist Episcopal church in town.

“On a hot dusty day, you can still see a slight depression on the property where the foundation was, and where the ground was pressed down at the front door from people walking in and out of the church,” Burg said.

The African American population in Shippensburg “really exploded” in the 1860s and 1870s, according to Burg.

“By the 1870 census, Shippensburg was 10 percent African American,” Burg said.

It was a diverse group, he said, composed of former slaves who were born here and later received their freedom, people who had lived here as free men and women throughout their lives, and others who had migrated from the South.

“Because of its geography, the Cumberland Valley provided a natural route for African Americans from western Pennsylvania, western Maryland and western Virginia to come north,” Burg said.

Although slavery was outlawed before the turn of the 19th century in Pennsylvania, blacks and whites did not live as equals for many decades to come.

“Like slavery, segregation was not just a Southern thing,” Burg said.

In Shippensburg, as in many other towns, “it was not a matter of law, but more of social customs and practice.

Some things were segregated and some were not. You kind of had to grow up in the town to know what was and what wasn’t.”

Pennsylvania passed a law ending segregation in schools in 1881.

It took Shippensburg more than five decades, until 1936, to fully comply with the law.

“The high school became integrated earlier, but the elementary school was not until 1936, when a new school building was built,” Burg said.

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.