Learning a second language can be difficult even if you pay for tutors, take classes and invest in costly computer tutorials. But imagine picking up a tattered Chinese/English dictionary in a refugee camp after escaping war-torn China at the age of 9 — and teaching yourself.

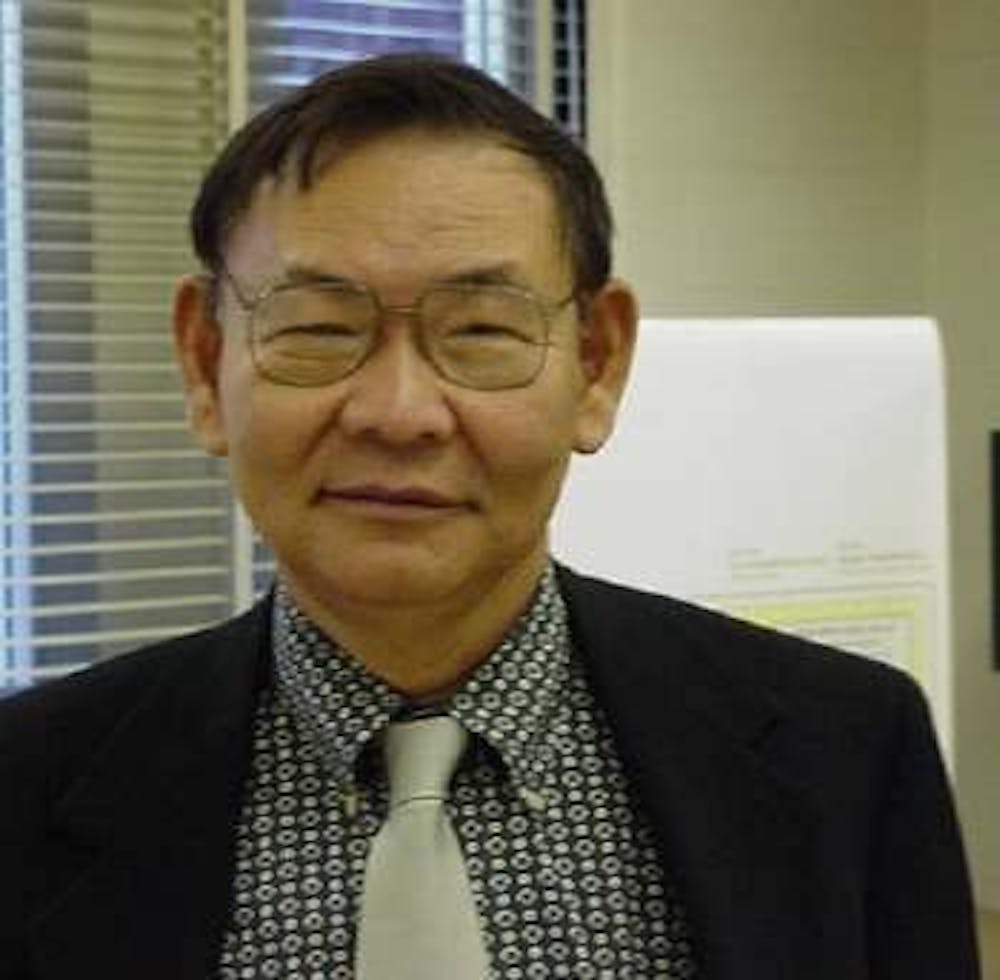

That is how Nathan Mao, who died on Feb. 1, learned English. He became the second most senior faculty member at Shippensburg University and taught American literature for more than four decades.

Mao, 73, succumbed to organ failure after successfully beating lymphoma cancer. While on sick leave last fall semester, he routinely received chemotherapy in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, until he was cancer free in December 2014. Shortly after, he was admitted to John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland, where he died due to liver failure in the presence of family.

Catherine Dibello, an SU English professor who knew Mao since she was hired in 1983, said Mao fought off cancer once before around 2004. According to Dibello, Mao felt like he was given a gift to have beaten cancer and get back to his life of teaching.

“He was glad to be alive and glad to be at Shippensburg,” Dibello said. Mao loved to teach and help students and was described as always upbeat and cheerful.

Born in China in 1942, Mao was raised in a time of political and social turbulence. Not only was China invaded by Japan in the 1930s, but it was also split by a civil war between the Communists and the Nationalists.

At some point in Mao’s early life his father left for Taiwan, while Mao and a family member headed to Hong Kong to escape the war and social upheaval. The two went to a refugee camp, where his interest in the English language and American literature took flight.

While attending the New Asia College in Hong Kong, Mao became increasingly devoted to learning about American literature and culture. After getting a degree, he moved to the United States to complete a graduate program.

“He always had this really strong drive to excel at everything he did,” Dibello said.

First, he went to Yale University and then he earned his doctorate in American literature at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1966.

In 1970, Mao began working at SU as an English professor. Over the years he became popular for writing and translating numerous books, most prominent of which is “Fortress Besieged.”

“Translation became what he was known for,” Dibello said, adding his version of “Fortress Besieged” is considered a state of the art translation.

Profiting much off of his hard work, Mao donated to both the Republican and Democratic parties over the decades, and in recent years he focused on supporting African-American organizations.

“He was very concerned with trying to help people — lots of people,” Dibello said.

Mao also gave money to the university, for which he had a room named after him in Old Main, and several plaques were posted in recognition of his charity.

The late professor was a strong believer in the American dream and was highly invested in politics. He became good friends with former U.S. Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania and met former President Ronald Regan and current U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, among other major politicians.

In the classroom, Mao paid particular attention to each of his students to ensure their educational success. He made a strong effort to learn every students’ name, speak with them and give them access to as much educational material as possible.

“He had a very strong philosophy that all students, regardless of their background, deserved the chance to receive an education,” Dibello said. “He would always say, ‘this is America, everybody should be able to get an education.’”

Mao’s personal experiences drove his passion to educate students. Shari Horner, English department chair, described him as a fantastic story teller.

“He was just great at making those personal connections and telling stories,” Horner said, adding that his own history of being an immigrant was used to enlighten his students in different ways.

The story of Mao came to end on Feb. 6 at the Chapel of Thomas L. Geisel Funeral Home in Chambersburg where services were held in his honor and memory.

“He had no interest in retiring,” Horner said. “He wanted to teach up until the end.”

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.