A University of California professor unraveled how modern-day discrimination persists in cities like Baltimore, Maryland, because of their complex history, while speaking in Old Main at Shippensburg University on March 28.

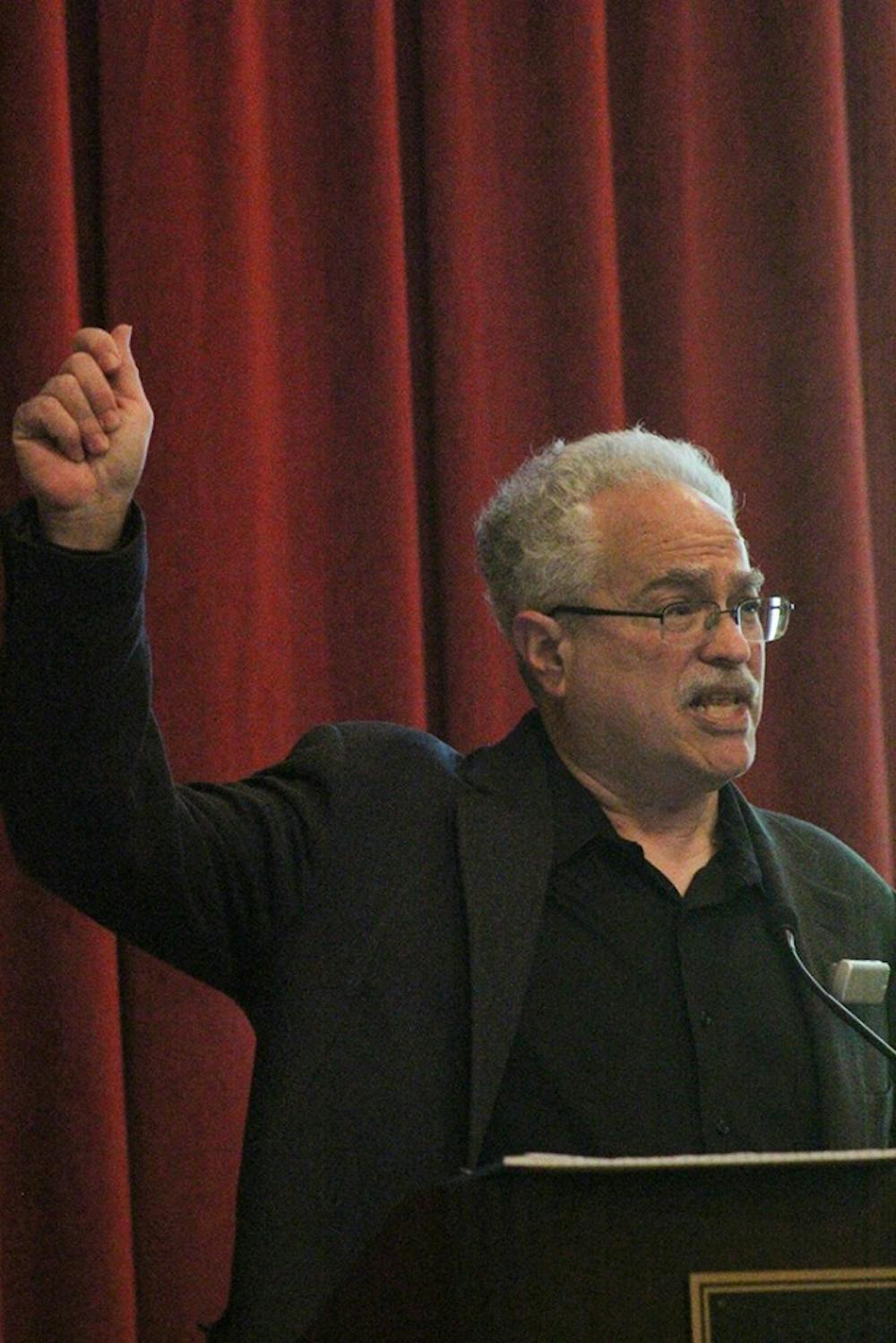

Professor George Lipsitz, who spoke to more than 100 SU students and faculty, is a professor of the University of California, Santa Barbara. He works in the black studies and sociology departments and has a doctorate in history. Lipsitz advocated for the importance of humanities and social justice in his presentation, “Justice for Freddie Gray.”

“I want to talk about what it would mean to be on time with our time,” Lipsitz said, pointing out the challenges society faces today, and how they were brought about. “We’re facing something extremely difficult, and we’re not in a good position to deal with that because our society remains so segregated.”

One of the reasons society is still racially segregated is because of a long history that is plaguing the present, Lipsitz said. Redlining, a form of housing discrimination against the black community, is a common reason why modern communities are segregated and experience poverty and discrimination. Lipsitz grew up in Patterson, New Jersey, and said he experienced housing discrimination first-hand.

“The city, in some ways, never recovered,” he said, noting that violence erupted as a result of the segregation. “Housing discrimination has been against the law since 1968, but that law is broken every day.”

In some cities, such as Baltimore, there were once federally backed contracts stating white homeowners would only sell or rent their property to other whites. Other laws only allowed people to move to a neighborhood if the majority of their race was already present. The result, Lipsitz said, is that black and Latino communities are often subjugated to neighborhoods with low and depreciating property value, creating a cycle of poverty and a lack of opportunity.

Freddie Gray, the Baltimore resident who died while in police custody after alleged mistreatment and discrimination, lived in a neighborhood that saw the long-lasting effects of housing discrimination, Lipsitz said. Gray’s former community, Sandtown-Winchester, has 52 percent of its population unemployed, 33 percent of its homes vacant and 7.4 percent of its children with high levels of lead in their body, according to Lipsitz.

History, Lipsitz said, has everything to do with why Gray grew up in an under-developed neighborhood and why he was treated poorly. History explains why police officers drove Gray down rough roads and intentionally inflicted harm on him, while riding in the back of a paddy wagon, Lipsitz said.

“To understand that 60-minute ride, you need to understand 60 years of racialization in Baltimore,” he said. “You need to see how things got to be what they are. Which is one of the things that history, one of things that the humanities has always professed to teach me, is that part of what things are is how they came to be.”

The humanities are what students of the college of arts and sciences often study. They are there to train people to be good citizens and promote justice in a society, Lipsitz said. They interrupt habit, promote empathy, resist single-mindedness and envision a common and creative existence.

In reality, the humanities were misused and abused to invent a hierarchy of humans. Particularly Europeans in the past few hundred years created the idea that one culture and way of life is superior to another. This mentality was what was used to discriminate against Native Americans and eventually African natives.

“They invented the primitive,” he said, adding that the people who created the humanities were often judges of others. That kind of thinking started large-scale discrimination and segregation. The effects are still lasting to this day, and this is what causes modern race problems, he said.

SU junior Jessica Hogan applauded Lipsitz and said his explanation of the history of race relations is linked to today’s problems. She said that one problem SU faces is that some people are not aware of the challenges black people have and think that opportunities in life are not based on race.

“They say black people are the same as white people because they have the same opportunities,” Hogan said. “They don’t know what the struggle is, or what we have to go through.”

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.