With outstretched arms, Christopher Kovats-Bernat, an American anthropologist and one-year visiting anthropology professor at Shippensburg University, brought to words the tattoos that adorn his skin from elbow to wrist. The Haitian flag, Voodoo spirits and phrases penned in foreign script are among the eight.

He carries these spirits and symbols on his body much like a soldier who clothes himself or herself with armor before heading to war, as he was told by a Voodoo priest in Haiti that they will protect him from harm. But internally, Kovats-Bernat carries with him much more than what is visible. He carries tragedy, altruism, gratitude and persistence, all of which he acquired during his travels to and from Haiti over the past 24 years.

Since his first trip in 1994, Kovats-Bernat has spent nearly six years in Haiti, with some stays as short as a week and others as long as nine months. He most recently traveled to Haiti in the summer of 2017.

Kovats-Bernat spends his time in Haiti studying its people and becoming one with them, so he can understand their cultural phenomena and craft a written record of their customs from an internal point of view.

For the last four years he has been completing fieldwork on Haiti’s Voodoo, witchcraft and zombification practices, but his initial project was with Haitian street kids, a subject of interest that he attributes to his rough upbringing.

Kovats-Bernat collects sacred water from a Voodoo shrine in Haiti, where he is conducting fieldwork on local Voodoo, witchcraft and zombification practices.

Drugs, violence and inescapable poverty lurked the streets of Kensington, a working-class neighborhood in Philadelphia — the place that Kovats-Bernat called home as a child. His house provided minimal protection from the harmful world on the other side of its closed doors, as his abusive father, too, acted with hate rather than love.

In pursuit of a better life for her children where the cycle could not repeat itself, Kovats-Bernat’s mother relocated him and his siblings to Allentown, Pennsylvania, where he still lives. Kovats-Bernat was among the first in his family to graduate high school, college and eventually, graduate school.

He attended Muhlenberg College during his undergraduate studies, majoring in philosophy and minoring in anthropology, since the college did not have an anthropology major at the time. While the minor only got his toes wet, Kovats-Bernat knew from the introductory anthropology course he took his freshman year that anthropology was what he wanted to do for the rest of his life.

“I liked the idea that there was absolutely no restriction on what I could do with anthropology,” Kovats-Bernat said. “I could literally throw a dart on a map and say, ‘I’m going to go there,’ and open up a dictionary on any word and say, ‘I’m going to study that.’”

However, Haiti was not just the luck of the draw for him — he got some guidance. Aware of his interest in violence and children, Kovats-Bernat’s academic adviser at Muhlenberg suggested he read up on Haiti, which was experiencing ongoing political violence since the overthrow of its president in 1991.

After completing the readings, Kovats-Bernat was taken off guard when he asked his adviser, “What now?” And the response was, “Go.”

“I told him, ‘I can’t do that. I don’t speak the language. I don’t know anyone there. I don’t know what I’m doing.’ He said to me, ‘How do you know if that’s where you’re going to work unless you go?’ So I did what he said. I booked a ticket and I went,” Kovats-Bernat said.

The two-hour flight from Miami, Florida, to Haiti was not enough time to prepare Kovats-Bernat for the overwhelming sense of unfamiliarity he was met with when he stepped off the plane.

“The first thing that hit me was incredible heat. I had never felt heat like that before,” Kovats-Bernat said. “Then, I heard this cacophony of voices in a language I didn’t understand, and the only reason I got off the plane was because there were people behind me getting off, so I just kept walking.”

Dodging dead bodies and armed men on the streets, he said he followed the lead of locals flagging down taxis and navigated to where he was staying by piecing together the little bits of Haitian Creole he knew.

When he got there, he made a beeline to the bathroom and vomited in the mosquito-infested toilet. Sick, defeated and alone, Kovats-Bernat said he ached to talk with his girlfriend, who is now his wife, but his phone did not work. He fell onto his bed and cried.

“Really the only way for me to get over the culture shock was to persist,” Kovats-Bernat said. “I knew that academically in the back of my mind, but in reality it was very hard to do. At any time I could give up, but there was also the fear that if I did give up, maybe I wasn’t fit for anthropology.”

For the rest of the trip he took his days in Haiti one at a time. Once he realized there was little gun violence in the neighborhood he was staying in, he started venturing out of his room to go for short walks — often only around the block — and buying items from artisans on the street.

Kovats-Bernat believes he may be the only anthropologist who has ever completed immersive fieldwork in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, for an extended period of time, because its violence makes it incredibly unsafe, especially for foreigners, and its poverty-stricken conditions are a breeding ground for many illnesses.

“I’ve had malaria three times; dengue; giardia, which is a waterborne parasite; dysentery; was bitten by a Cane spider and went into anaphylactic shock; and have been diagnosed with PTSD from my work in Haiti,” Kovats-Bernat said.

With time he recovered from many of the illnesses that infected him and was no longer debilitated with culture shock, but one thing he never fully grew accustomed to was the level of risk that accompanied him during his travels.

An unmarried man in the beginning of his career as an anthropologist, Kovats-Bernat, like many bachelors, said he felt indestructible to the dangers around him, as he had little to lose. However, after he got married he had two lives to consider instead of one, and the eventual births of his son and daughter brought a new level of meaning to the word “risk.”

On Dec. 15, 2014, Kovats-Bernat received a phone call that sent his life as he knew it tumbling down around him like an avalanche.

“My daughter, Ella, had the flu and went into respiratory arrest. She died on the way to the hospital at 10 years old,” Kovats-Bernat said. “That same morning I was notified that I got a grant from National Geographic to do fieldwork in Haiti, and she died. I lost all desire to go back to Haiti, but I knew at some point I had to. When’s a good time to go back to Haiti when you just lost your daughter?”

Knowing a “good” time would most likely never come, he returned a few weeks after Ella’s death.

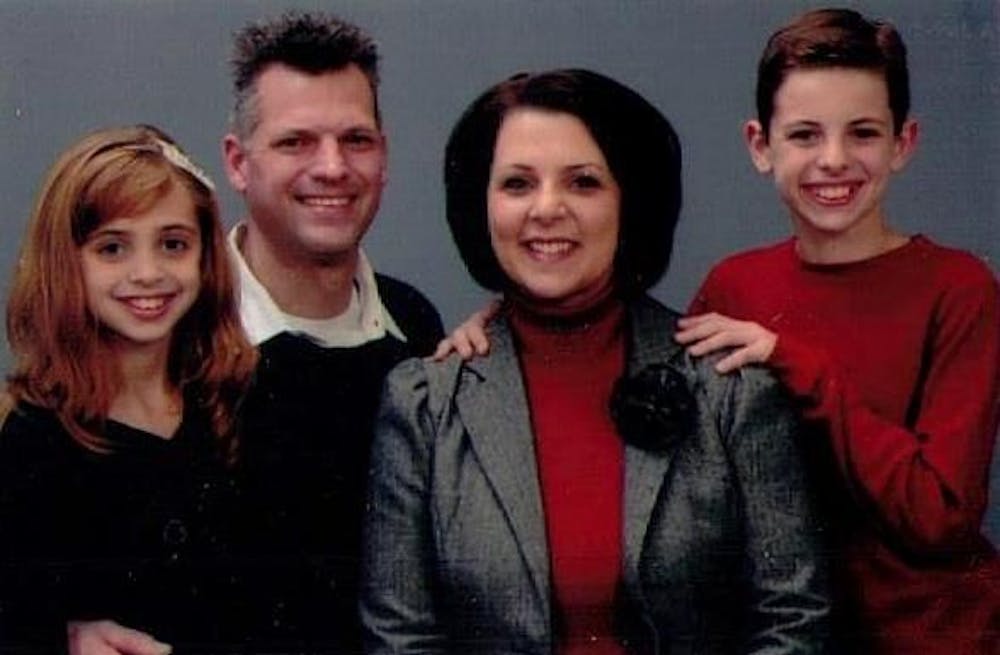

Kovats-Bernat's wife, Dina, has supported Kovats-Bernat through the struggles anthropology brought him, such as culture shock. Pictured with him and his wife is their daughter Ella, who passed away in 2014, and their son Addison.

During this trip and the several others that followed, Kovats-Bernat struggled to work with the same passion he once did, as the time away from home haunted him with guilt. In search of the strength he needed to refocus his life, he recounted a conversation he had with a Haitian woman after a catastrophic earthquake shook the country to rubble in 2010.

“There was a woman who was squatted down doing laundry and she had five kids running around. One of them was a 12 or 13-year-old girl who was severely mentally disabled. That was her sister’s daughter and her sister died in the earthquake,” Kovats-Bernat said. “I asked her, ‘I guess it must be difficult now, huh?’ Which was a stupid question, because how could it have been easy? But she looked up at me beaming, smiling, and she said, ‘Yes, the earthquake took much from me, but God protected my children, and children are like sugar in my coffee. They make sweet all that is bitter in this life.’”

This interaction reminded him that although the word “loss” may imply a sense of dispossession, it does not mean life after loss has any less value than it did; he still has a lot to be thankful for.

“I lost my daughter, but I still have my wife and son,” Kovats-Bernat said. “I learned that when everything gets taken away from you, family is what you have. Every day I am grateful I have my wife and son and I am grateful I had the gift of my daughter Ella for the 10 years I did.”

In between his travels to Haiti to complete fieldwork and weekends home with his family in Allentown, Kovats-Bernat makes a weekly commute to Shippensburg — staying locally Monday through Friday — to share his knowledge and experiences with SU students.

He previously taught for 14 years as a tenured faculty member at his alma mater Muhlenberg, but was growing tired of his work at the small liberal arts school. When his daughter passed he said he saw it as a sign to step away and pursue other passions. He stayed in the education field, but spent the last three years teaching kindergarten.

“With the loss of my daughter, I needed some time, and I took it. It was really nice working with the little kids for three years, but it was time to get back to the university. Like I said before, my whole life from freshman year on, I wanted to be an anthropologist, which means I wanted to work in a university setting, do research and teach,” Kovats-Bernat said. “When I was invited on campus for an interview this summer, it just confirmed for me that Shippensburg could be my home for a year. And I’d love to stay here longer.”

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.