For some Shippensburg University community members, the COVID-19 coronavirus is nothing more than an inconvenience requiring them to wear masks. Some are lucky enough have no personal connection to the virus. But for many families, the numbers read by news anchors each evening are more than numbers: They were mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters.

SU management professor, M. Blake Hargrove, lost his father in March from coronavirus complications.

Hargrove shared his family’s story on Sept. 17, days before America reached 200,000 deaths, according to the Associated Press. As of Monday morning, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 229,932 deaths in the United States.

Hargrove teaches in the John L. Grove College of Business, and said he wanted to share his family’s story to give SU students a name and a face to think about the virus. And he is encouraging SU students to take the virus seriously.

Hargrove explained that there are some students who are “paralyzed with fear,” while others who are seemingly unconcerned with the threat of the virus.

“But I obviously, personally, know that it’s real,” Hargrove said. “Things are weird, and life is disrupted because of COVID. And you know I miss my Dad.”

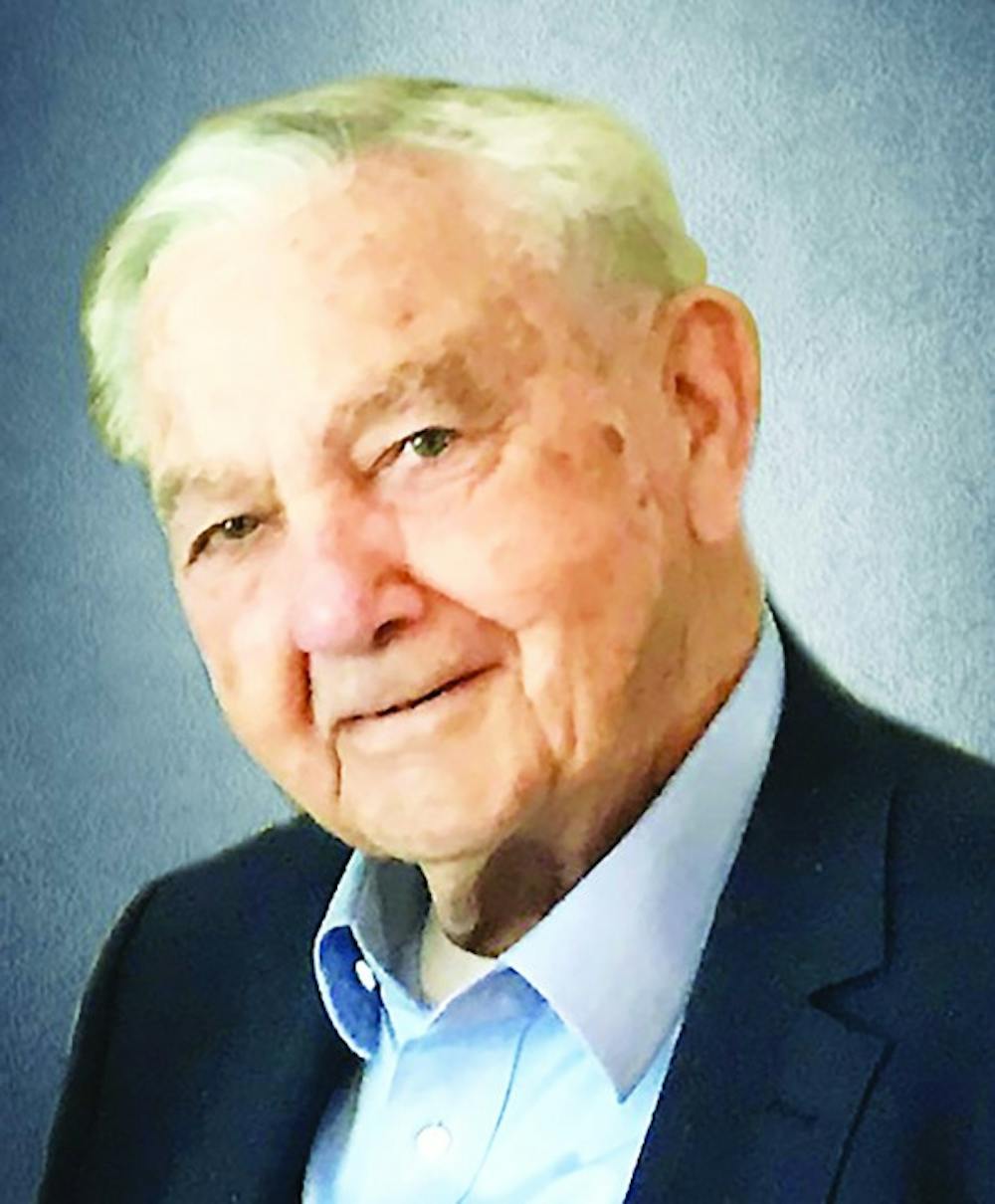

Hargrove described his father, Cecil “Mac” Hargrove, as a curious, intellectual, caring man, who had a passion for learning about the world around him.

Mac attended law school for a while but did not become a lawyer. He also went to seminary and served as a preacher in a small Texas town, before becoming a real estate investor.

Mac also had several opportunities to meet and interact with Martin Luther King Jr., of which his son said were life-shaping for his father.

Hargrove said his father worked well into his 70s, but always made time to enjoy art and opera music. Mac, and his wife of 63 years, Katherine, held opera and symphony tickets for their whole life together.

Mac and his wife would spend their mornings in their Dallas, Texas, home reading the New York Times and the Dallas Morning News, passing sections back and forth to one another. Hargrove noted his father’s yearning for intellectual growth and curiosity, given his love for reading.

“He was a searcher; he was looking for other people’s perspectives. And it was really interesting to watch him in the last couple years because he was really, heavily, intellectually engaged in people’s ideas,” Hargrove said. “He was really committed to beautiful things, and really committed to learning and finding what it was to live the good life.”

Hargrove said his father’s death in many ways is probably the way he would have wanted to go out.

“Getting to see these beautiful places that he’d never seen before, getting to see these works of art that he had never been able to see and getting to experience a city that he’d never seen before,” Hargrove said.

Hargrove was on a sabbatical last year and went to Spain as a Fulbright recipient. His parents and other family members were set to visit him in the country, as the coronavirus began to take over the news headlines.

After getting clearance to travel from doctors and receiving updates from CDC and Department of State officials, Hargrove said the United States government said it was safe to travel.

“We calculated the risk based on the information we had,” Hargrove said. “I think if our government responded in a different way, I would have acted in a different way.”

Hargrove shared his frustrations with the Trump Administration’s handling of the virus. Days before Hargrove’s interview with The Slate, journalist Bob Woodward revealed tapes recorded in February where the president acknowledged the threat of the virus.

“We were prepared to take calculated risks, and my dad was prepared to take calculated risks,” Hargrove said. “We did take a calculated risk, but our calculation was skewed by our government’s mismanagement.”

After watching the spread of the disease and listening to guidance, Hargrove said his parents flew to Spain on March 6. While abroad, Hargrove said he and his family were able to see some of the city, however, the coronavirus cases grew quickly while they were there. Officials had not mandated the use of masks yet. The Spanish government shutdown nonessential businesses, and after the Hargroves left became much stricter with social gatherings to attempt to stop social transmission.

When returning to the states on March 14, Hargrove said they took every precaution to try and limit their social interactions, using a private car service from New York to Pennsylvania.

After returning home, Mac did not show any symptoms until 10 days after exposure. At least five of the six members of the household tested positive for the virus, including Mac’s 82-year-old wife. Hargrove said she had a couple days of lethargy, while his own wife lost her smell and taste senses and he had a headache. Hargrove’s two daughters were asymptomatic. One daughter had flu-like symptoms, but never tested positive.

Hargrove drove his father to the hospital and checked in around 3 p.m. and his father died around 7:30 the following morning. He said his father’s death was, “pretty swift and painless.”

He said the family was grateful for the nurses, especially the two who committed that they would hold their father, grandfather and husband’s hand when he died. Hargrove said his father died during the shift turnover time and actually had a nurse in each hand.

“You know it is really comforting and sweet, but it also wasn’t us. It wasn’t my mom; it wasn’t me and my brothers or his granddaughters. It was two strangers,” Hargrove said.

Hargrove said he does not feel overwhelmed with guilt but said he does not like the connection between his decision and his father’s death.

“But it’s pretty incontrovertible that had I not had a Fulbright in Spain, and they wouldn’t have gone to Spain,” Hargrove said. “And I know what would be heartbreaking for any Shippensburg student, whatever their politics is to contribute to the death of their own parents or grandparents.”

Hargrove said he wanted for students to hear his family’s story to recognize that the daily coronavirus death numbers are more than a number — they are a family member.

“This is a real story, it’s a real thing and then if they don’t take it seriously, it’s not just going to screw up their college experience,” Hargrove said. “COVID does not care whether you believe it or not. The virus does not care whether you think it’s a real thing. If students behave like it’s not a real thing, and they go home for Thanksgiving dinner where their grandparents don’t think it’s a real thing, they can kill their grandparents [through exposure].”

Given that that a lot of SU students live central Pennsylvania where families tend to have Thanksgiving dinners with more than their individual households, Hargrove encouraged students to think before acting.

“Take advantage of free testing and give up on partying and going out,” Hargrove said.

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.