Ezra Lehman Memorial Library hosted the official opening of the international traveling exhibition “Names Instead of Numbers” to honor and remember the victims of the Holocaust on Nov. 14.

Action Reconciliation Service for Peace (ARSP) displays the names and stories of victims who were part of the 202,000 prisoners taken into the Dachau concentration camp between 1933 and 1945. Through these exhibitions, ARSP shares biographies of the victims.

The moving exhibition displays a selection of biographies from the Dachau Remembrance book, an “ongoing, extensive collection of biographies of former prisoners of the Dachau concentration.” The project has been in operation since 1999 and is written in multiple languages.

The book and exhibit includes the names of those imprisoned at the Dachau concentration camp, located just north of Munich, a city Adolf Hitler labeled as the capital of the Nazi movement. Dachau was also the first camp in what would become a network of concentration camps stretching from France to Ukraine.

Upon arrival at any concentration camp, prisoners were forced to exchange their names, clothes and valuables for a uniform and a number as their only means of identity.

The introduction to the book says, “through these measures, the National Socialists attempted to take away each person’s identify and dignity.” The book and its contributors aim to counteract that by recording their stories.

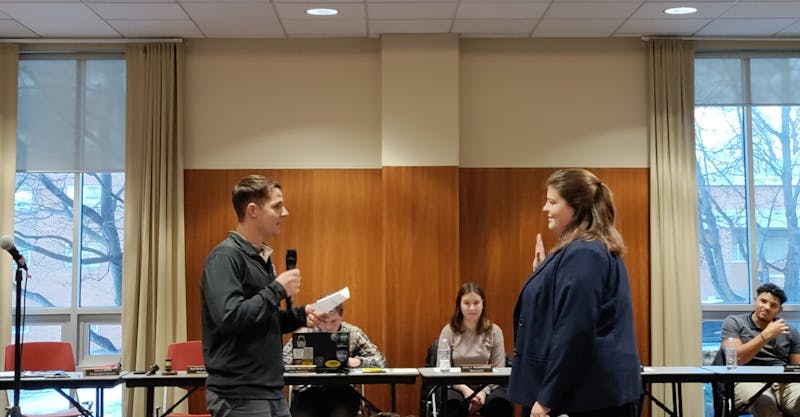

The two speakers at the exhibit were Dr. Monika Moyrer, the U.S. Program director of ARSP, and Shippensburg University’s Dr. David Wildermuth, associate professor of the Department of Global Languages & Cultures. Wildermuth specializes in German and Austrian history, as well as the Holocaust.

Wildermuth alluded to America’s issues with antisemitism, referencing FBI Director Christopher Wray’s testimony.

“While Jewish-Americans make up less than 2.5% of the population, they accounted for over 60% of victims of religious hate crimes,” Wildermuth said.

Wildermuth finished his presentation saying, “This exhibition reminds us where the road of discrimination, racism and anti-Semitism leads.” He continued, saying, “If we are not moved to remember this by lofty appeals to our better nature, then perhaps through the naked self-interest epitomized in Niemöller's poem.”

The poem, “First they came…” was written by Martin Niemöller, a Dachau prisoner and Protestant minister who initially supported Adolf Hitler. He himself was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp and later Dachau for opposing Nazi policies.

The poem reads, “First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me.”

After he finished, Moyrer took the stand to give her remarks on the exhibit. She began with a quote from Spanish philosopher, George Santanya, that rings true with the exhibit, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

It is this characteristic of remembrance that Moyrer wishes to uphold as a German person.

“We Germans are often praised for our politics of remembrance, that we have come to terms with the past and we are dealing with it,” Moyrer said.

The Dachau Remembrance catalog is a step in that direction and to building a more positive relationship between Germans and those of Jewish backgrounds.

Moyrer hopes that these acts of mourning, remembrance and honoring will “rebuild trust through symbolic gestures and forging close ties with Jewish people and with, of course, other communities.”

Moyrer expressed how much these exhibits mean to her and how important these means of education are to create social harmony.

“As we are assembled, look at the biographies of former prisoners Dachau, we participate in the exercise of humanizing them, of giving them back their dignity. Thank you for being here. It is a small gesture that goes a long way. Let's honor those who have suffered tremendously and not forget those who suffered today,” Moyrer said.

Wildermuth added that honoring those at universities like Shippensburg “helps us to combat any notions of 'the other' that might form due to the inability to get out in the world and realize that we all share a common humanity.”

The Slate welcomes thoughtful discussion on all of our stories, but please keep comments civil and on-topic. Read our full guidelines here.